On the particular

William Bronk, Vito Acconci, and Stanley Brouwn

I’ve been thinking lately about the particular, and about these three pieces:

1) William Bronk, from his book of three-line poems The Force of Desire:

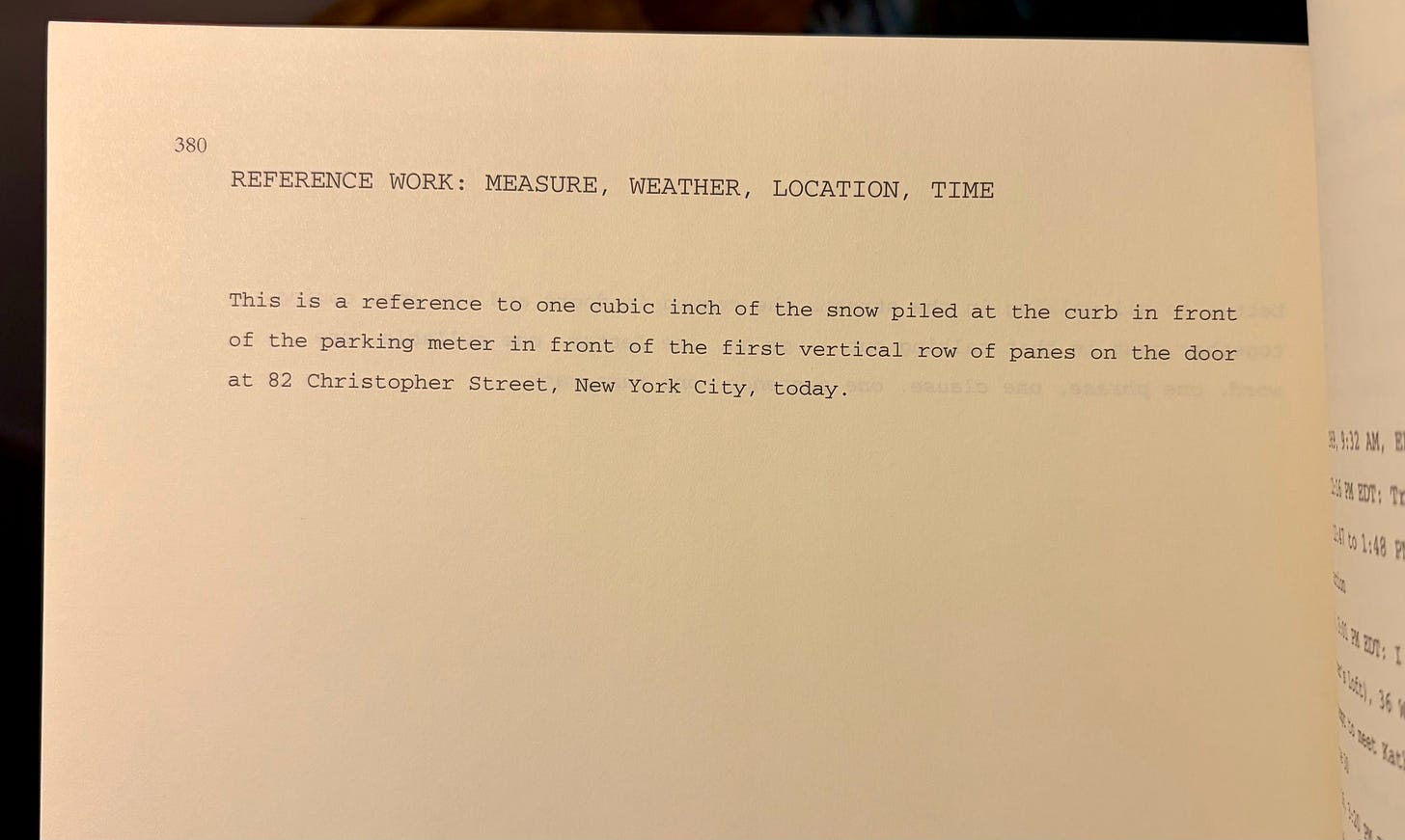

2) This piece by Vito Acconci:

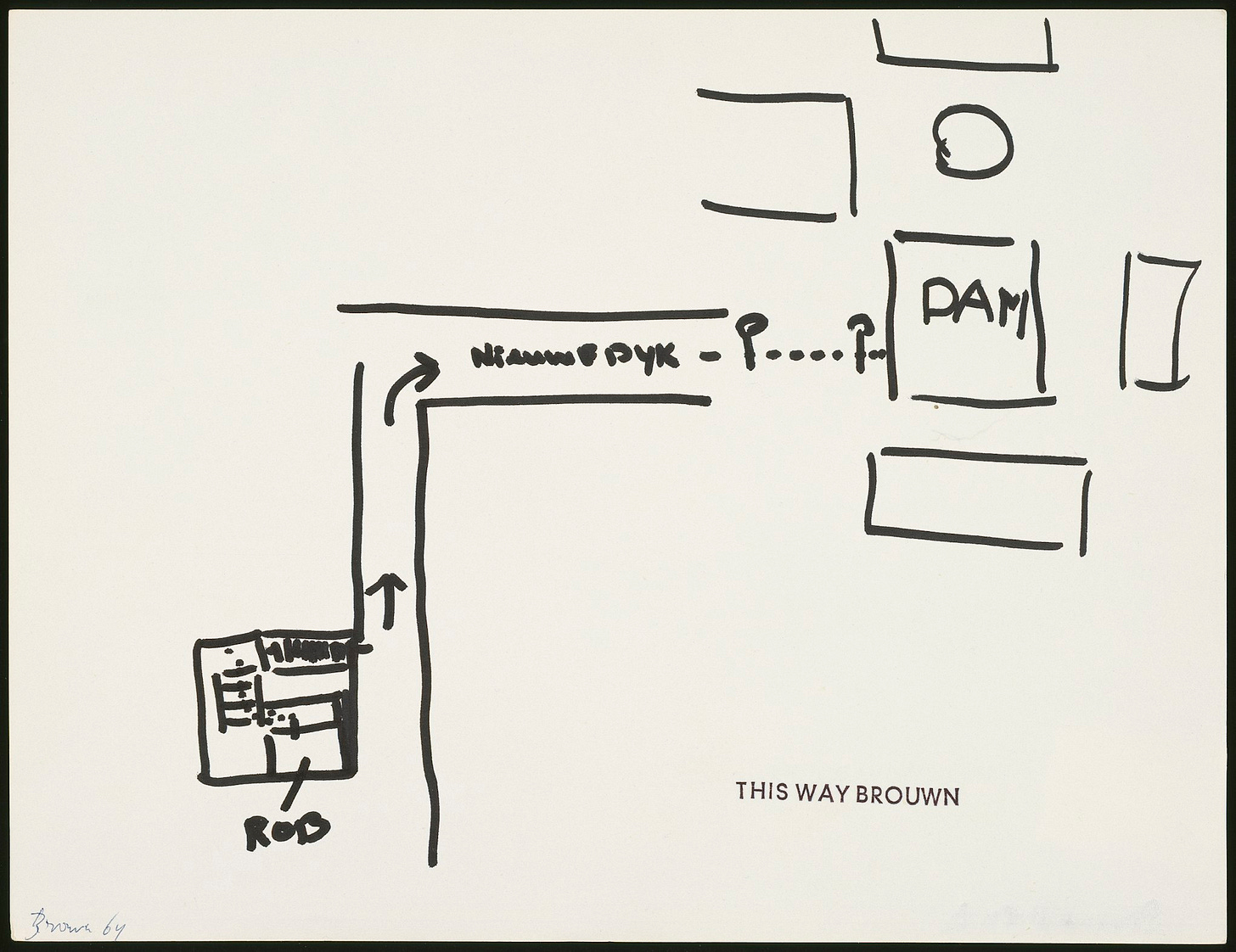

3) Stanley Brouwn’s This Way Brouwn, which you can learn more about here. (I found out about Brouwn and his work from Martin Herbert’s excellent book Tell Them I Said No, which if you’re looking for a post-holiday book to self-gift, that’s the one!).

I remember being in college and really feeling like I’d been hit over the head with something big when I realized that universals(/abstractions,/ideals,/etc.) sometimes hurt more than they helped. I knew I wanted to be a math teacher, and math-ed social media was full of anecdotes about how well-intentioned efforts at education reform had created serious problems for actual educators and their real students. I read about how lofty principles were leading to hours and hours of high-stakes testing for students, and heard from math educators how they felt unable to emphasize research-backed, student-centered, discovery-driven aspects of their practice because their evaluations (and, thereby, their livelihoods) stood and fell on how well they could teach to a test. I’m oversimplifying a lot of complicated conversations in education, here, but all I want to communicate is that there was something incredibly appealing, by contrast, in the narrow focus of the particular: “local solutions to local problems.”

In an assignment for an education class, I remember quoting this snippet from Deleuze: “A universal explains nothing; it, on the other hand, must be explained.” The thing that would do the explaining of the universal, I imagined, were many many sets of concrete circumstances—in other words, a universal or an abstract idea would make sense only if it spoke effectively to lots of real people and real situations in real life. For me as a very very novice teacher, this meant I had a lot of work to do to get to know the community I was teaching in, and then I could look sidelong at any Big Educational Principles™ because I’d be measuring them against the actual experiences of the people in that community. This, I thought, is the way, and it is clear.

Back to the three pieces for the moment: I think that the allure of the particular comes, in part, from the idea that it seems so knowable. William Bronk, author of 1) above, lived in Hudson Falls, NY for the lion’s share of his adult life. He walked the same paths daily for years and years, knew many of the townspeople through his family and his family business, and certainly would have had the strongest possible sense of the place. Bronk was also a master ironist, so I’m very far from suggesting that we should take his capital-U invocation of “Ultimate reality” at face value. Rather I think Bronk is offering us a tongue-in-cheek reductio, in two ways: first, the poem posits this place, which poet and speaker know better than anywhere else on the planet, as “Ultimate reality”. Then, after encrypting it in the cipher of a “zip code”, a literal number (what better figure for the real passing into the abstract?), something curious happens: the poem shifts from the third-person declarative mode of its first two sentences to a quick one-two punch, on the same last line, in the second person:

Write to me. Here.

Why would ultimate reality need to be written to? Is it ultimate but somehow insufficient? Also, I love the way this little poem ends: Here. For a long time I read that Here as being entirely a recapitulation of the zip code from the previous line, only this time indexed by the speaker: a zip code stays in one place even if the speaker leaves it (or dies), but the Here requires somebody fixing the reference of the adverb, like what in type theory is called a witness. Lately, though, I also want to read this little word—needless to say, homophonous with hear—as the same word you would say if you were handing someone blank paper and a writing utensil with which to write a letter. Here, like G.E. Moore’s Here is one hand. It presupposes an audience you want to talk to, write to, prove something to. Or that you want to give something to.

(A quick aside: the slipperiness of the particular was also something I learned about firsthand as I got further and further ensconced into my first teaching job. Any first-year teacher can tell you about how many cans of worms you’ve opened by October.)

This paradox, in which the particular gets more and more singular and specific just as it slips away from us, or requires another pair of eyes to confirm what we are seeing, deepens when we face up to how fragile the singular image can be. Vito Acconci’s “Reference Work: Measure, Weather, Location, Time” feels as cut and dry as is possible for a reference work: it picks out “one cubic inch of […] snow” and, like Bronk’s zip code, gives us enough description to, in theory, spatially locate this tiny white cube on the streets of NYC. But also like Bronk’s poem, we are stopped cold with the closing indexical: today. Acconci’s spatial description baroquely folds in triangulating references to so many surrounding objects—the curb, the parking meter, even individual panes on the door—but the “Time” in Acconci’s title is trusted entirely to a word that must be inhabited by a writer, a speaker, or perhaps a viewer. This single person, like Bronk’s aspirational letter-writer/addressee, has to hold the parallax view of the particular space of the poem and play a kind of external role, one of attestation—that what’s described in the piece is actually there, that it can be found.

This (brief aside: “This,” also an indexical, is an overlapping word between 1), 2), and 3)) brings us to 3), Stanley Brouwn’s piece This Way Brouwn. Before we spend some time with this very interesting work of art, just one more note about the difficulty of writing as a form: when you write something, you naturally hope a reader will have a response to it. But the shape of that response is, in line with the difficulties we’ve seen with 1) and 2), paradoxically foreclosed: the writer-reader relationship doesn’t always give the reader space to respond openly to the text. (Nothing is stopping you from writing in the margin, but many of us don’t; sometimes that response lives all & only in the reader’s head.) Or it can amount to an invitation to trade places: to write something new in response to what one has read, and become the writer oneself, in a new iteration of the relationship. The worst case, to my mind, is when writing seems to want to steer the reader’s response with an overly strong hand, manipulating emotions or browbeating with a kind of clunky morality that puts the reader in the position of only really getting to say yes, I see, I agree. (Maybe something worth writing about in a future post—too wriggly a can of worms to open now, I think.) But an equally difficult case is when the writing is such a totally open field that any response seems like it could have equal ground—a couple of times when I’ve tried to write about certain, let’s say, very experimental works, I’ve felt their indifference to sense basically playing the role of a Rorschach, not willing in any way whatsoever to determine a reply. This is freeing, as a responding reader, but paralyzingly so.

Enter This Way Brouwn, in which:

What he [Brouwn] did was to ask someone, "How can I get from here to another point of the city?" And he would hand them a sheet of paper, with a pen or a pencil. And, the passerby was asked to make the drawing. And what Stanley Brouwn did was to ask similar directions to different people. So on one side, you see someone who is telling him with very geometrical line how to cross the city, and someone has a much more smooth, fluid way of crossing the city. (Christophe Cherix, MoMA curator)

The premise of This Way Brouwn is beautifully simple and irreducibly participatory: like many of Acconci’s later works, it only takes its proper shape in the hands of people who are not the artist. Take a second to image-search “This Way Brouwn,” and enjoy for a moment the sheer variety of map-direction artifacts that were produced over the course of Brouwn’s project. (This one is a particular favorite.) One of the aspects that makes the piece so compelling is that Brouwn’s “ask” is a seemingly closed task: just asking for directions from one place to another. If both parties had a map there’d be nothing here at all, just a finger dragging along prescribed streets. But the way Brouwn invites the participants to put, not just their directions, but their whole mental models of the city on the paper—to me, that’s the real there there. The particular felt so straightforwardly knowable, earlier, in contrast to unwieldy universals, but suddenly now we see how people have come to know that particular: concept-ladenly, through a framework that leaves its fingerprints on the glass of perception. These maps in folks’ heads would be jarring if they didn’t gel with our own—or, if you’re like me and haven’t been to Amsterdam (in which Brouwn occasioned This Way Brouwn), you can admire how they simply sing with unbridled plurality.

(I’m no longer a math teacher, but I still work in math education, on curriculum. Right now I am working on a project that involves looking at lots of student responses to mathematical questions; if you have ever given into the popular myth that math is “black and white,” or “just right and wrong,” there’s really nothing like looking at thousands of middle- and high-schoolers’ responses to math questions to realize that math is a space of creativity, play, and way more 6’s and 7’s than you’d ever imagine.)

So the particular, then, is not exactly a stable, fixed, known thing. Instead it is a bit more like an invitation—look, here is this common experience we’re both having in space and time; tell me about it, from your end of things. Draw me a map to it. Find one cubic inch of it worthy of comment amid all the other things to attend to. Write to me. Here. Know I’m asking earnestly, wanting to know your answer, or answers. That, I think, is the open secret to all three of these works: Brouwn, whether or not he actually went to the places his participants drew him directions to, was interested in the shapes of their paths. Bronk, acerbic though he could be, had the warm heart of a practiced host, and I think his speaker means it when he sings Write to me. And as for Acconci: we know audience comes to its primary importance for him later in his career, but still, this early written piece is a “Reference Work”; in order for a reference to be, in any way, useful, it needs to be taken up by someone else in the future. I applaud the future that all three of these works anticipate, where the particulars they’ve chosen to attend to still matter, still concern others, & will be taken up in kind.

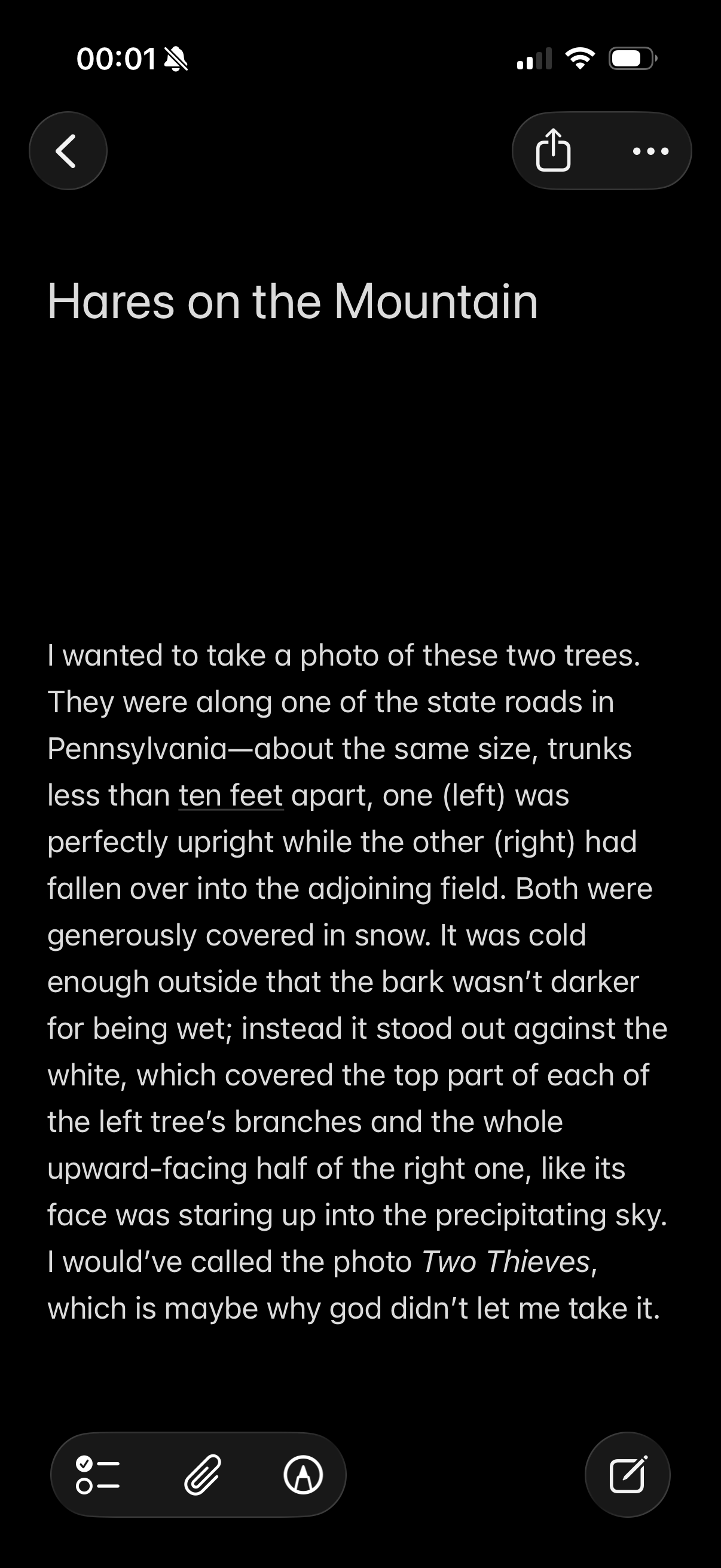

I’m trying to get better at thinking of this Substack as a more heterogeneous space—not just poetry, but also math, & also philosophy, & also (maybe) new creative work. Here is a small prose poem that came out of today’s post (title from here)—thank you very much for reading, and for your continued support in 2026; it means the world! :)

ALWAYS so fascinating to read ANYTHING you write & take a little credit for the nurturing that created your Brilliant Brain! 🤩🥰

Kant was right, right? You can only perceive particulars through universal categories. I've been thinking a lot about particulars in my reading lately -- John Cheever and Mary Gaitskill seem to have limitless stores of amazing particulars to tell their stories with. Where do those come from? How can I better tap into my own reserves? But when I read those stories, somewhat paradoxically like you're saying, you feel the particular perspectives of the storyteller on the characters...which is definitely *not* particular but full of moral and character judgement. But I think this is maybe a bit of a trick -- by giving us all these particulars, dropping in a subtle guiding abstraction or two, and inviting us to participate in the perspective, we end up having better access to the universals.

One hell of a trick! And I think something like this happens with teaching also -- part of what's good about good teaching is sequences of particulars to prepare for abstractions/brief direct instruction of abstractions/a chance to apply the abstractions to new particulars.

Anyway, great post, and thanks for introducing me to these three works. (And the term 'witness'!)